To Ensure Perfect Action of The Machine

A fictional recounting of my grandmother’s journey as a garment worker in Chinatown, from the point of view of her Singer sewing machine

My maternal grandmother, Mok Sim Tsang, worked as a seamstress in Chinatown from about 1968 until she passed away in 1997, one year after I was born. Alongside thousands of other Chinese immigrant women, she made garments for piece rates paid by employers. She worked in a sweatshop at 50 Eldridge Street, and to save money, brought some of the piecework that she sewed with her machine home to dress my mother, aunties, and uncles.

My po po was born outside of Hong Kong in a village that no longer exists - it is buried under a diffusion of new development; an upscale amusement park and resort, not unlike the tide of development unrecognizably altering the small pocket of Chinatown Manhattan where my family secured a foothold in the United States.

When Ruth told me she was creating a literary magazine that explored experimental textile art and forms, I didn’t know what to contribute that would feel relevant to the concept—I don’t (not for lack of wishing) have very many textile-based talents.

This year has seen me embark on a personal expedition to get to know my mother’s parents, my gung gung, who passed in the 80s, and my po po, Cantonese immigrants whose work in their respective industries afforded future generations of their family to make it, here in the States.

I previously went searching for my grandfather’s now-shuttered restaurant out on Long Island in an attempt to know him, to better know myself. You can read it here on

’s The Desk Dispatch series.The piece for Frog Mag is a fictional recounting of my grandmother’s journey as a garment worker in Chinatown, told through the eyes of her Singer sewing machine. I am supremely grateful to Ruth, Masood, and the rest of the Frog team for giving this cross-generational exploration a place to live.

To Ensure Perfect Action of the Machine

Originally published in Frog Magazine Issue 1, August 2024

Singer was well-accustomed to an absence of natural light. She had spent much of her life in windowless factories—from the moment she came off the assembly line in Elizabethport, New Jersey her treadle was in constant motion.

The room in which Singer now sits is pitch black and motionless, save for a platoon of iron oxide molecules marching out from her gears ever so languidly, rusting her from the inside out. There are others like her here, largely forgotten relics adrift in the unforgiving river of time (though it bears mentioning inanimate objects don’t experience the flow of time in the same way as human beings, who, believing themselves to serve a higher purpose, often live their lives in pursuit of the posthumous, betting the house on the chance that they’ll eventually get to waste away in the Great Margaritaville In The Sky, all the while forgetting to truly live). The cosmological forces of time are too wobbly to be measured in terms of human lifespans, since, not that an inanimate object generally plans on this, they are all patiently, slowly, outliving us, even those we deem obsolete.

“Hard to wear out a Singer!” reads an ad from the year of her creation. She certainly felt like somebody had taken it upon themselves to see just how hard it might be to wear one out—after weathering nearly a century’s worth of broken needles, fabric jams, thread nesting, and extended use without a refreshing pour from her late (or lost) partner, Oil Can, she felt positively threadbare.

Singer often thought about time, reflecting on her observed experiences as an object once in constant use. The dark place she finds herself now is the basement of a museum in Manhattan’s Chinatown, a climate-controlled storage center of exhibitions past, full of paraphernalia waiting to perhaps once again be displayed in front of a mildly interested public, only a few blocks away from her former workplace and home.

For most inanimate objects (say, a lamp), locomotion doesn’t come naturally lest a human were to intervene, grabbing them by the “neck” to adjust or swivel or relocate, however, what one would refer to as the “neck” of a lamp is predicated on the human tendency to label everything within the context of their corporeal form—it’s really all just lamp. Technically, the lamp does have locomotion at the atomic level, an undetectable and constant flux of atoms and electrons and protons buzzing about in the chaos of space. Some, say a treadle-powered 1938 Singer Model 95-10 Industrial Sewing Machine, conspicuously locomote by way of a human operator. In stillness, there is great activity, beyond human comprehension, and the inanimate, those dust-collecting household objects we perceive only in our periphery, see all of this.

From the “neck” up, Singer boasted all the pre-mass-manufactured quality of a piece of machinery that today’s sewers might scour flea markets to collect and rebuild, similar in form to her frillier, more ornate cousins who’d been created to enmesh with the household furniture of the Dirty Thirties—her chassis, emblazoned with her namesake, curved up and over like some black primordial muck that had come alive and raised a newly-forming arm out of the swamp, at the last minute deciding against it, smoothing and hardening into a crooked position indefinitely. This curvature of her cast iron body telegraphed exactly where to find her finer points, from her stop motion wheel to her needle, clamp, and accompanying presser foot. The similarities with her cousins end there; rather than an intricate cast iron base, or perhaps a solid wood table that could double as a piece of entryway furniture for guests to sit their cocktails upon, Singer was slotted into a drab Monopoly-money-green sewing room work table with ruler lines painted down the length of its sides, sporting harsh gunmetal grey legs. Her accompanying treadle, a simple metal plate, looked like something a cowboy would find off the side of the train tracks and use to cook eggs over his morning campfire. A machine destined for the garment factory floor needn’t be pretty to create pretty things.

At first, the work proved to be enjoyable—Singer was a machine, after all, and superseding once-by-hand tasks is what she was created for. For just how long she danced the sweatshop tango she couldn’t tell, though dance she did, to a frenzying and unabated crescendo. She reveled in the idea that most of her days consisted of pecking and stitching textile into evocative forms far beyond the torpidity of simple reams of fabric and spools of thread (many of whom Singer had called intimate friends for a short time, their life span, unfortunately, linked very much to their diminutive size), creating beauty where there’d once been raw material. It was here, upon uniform rows of green sewing tables, where Singer and her mechanical sisters worked side by side from dawn to dusk, rehashing the day’s events after the factory lights went out—what kind of dress their operator had been tasked with constructing, how many needles they lost, who had pecked the fastest overall until the tubes of harsh fluorescent light switched back on and the platoon of middle-aged Chinese women returned to silently hunch over their sewing tables. The slog of sweatshop existence demanded reprieve in commiseration, a practice held up by both human and machine alike.

In time, like an American student learning their country’s history via the internet rather than their assigned textbooks, the grand illusion was dispelled. She resented even her modest part in this burgeoning empire of purported beauty built upon a gross depletion of resources and worn-out Singer sewing machines (knowledge she discerned from clandestine conversations between sweatshop workers after befriending her operator’s jade necklace, who took it upon himself to translate the juicier Cantonese gossip).

She was dismayed that her very existence enabled the exploitation of underpaid human workers and the destruction of a natural world known to her only through floral prints. After all, one can only sew so many tags into the collars of the same sports shirts for pennies apiece before realizing something isn’t adding up. She felt defeated—her capacity to create wonder had been supplanted by the insatiable American demand for cheap, superfluous clothing sold at margins that gouged customers and workers alike. She hadn’t been created to bring beauty into the world, no, she’d been created to further flood landfills with discarded clothing, to hasten humanity’s hurtle toward the end of the Anthropocene, to sow destruction. It’s a very fortuitous thing, then, that Singer was unaware that in 1939, the year after she was assembled, Singer’s (the company) factories were requisitioned for weapons manufacturing during the Second World War. She very well could have been a Colt .45 semi-automatic pistol.

Chinatown’s garment industry boomed in the mid-century, and so too did a demand for cheap, dupable labor. Waves of Chinese immigrants, predominantly women, arrived in New York City after the dissolution of targeted immigration bans in 1965 and found themselves with their pick of unforgiving, low-paid sweatshop gigs.

From an outsider’s perspective, the Chinatown sweatshop has long seemed an enigma too shameful to broach. Long hours, meager wages, hazardous and unforgiving conditions: were their owners evil, their workers victims? The truth proves to be far more complex—of the owners, some workers might describe them as carrying a benevolent harshness, a firm-but-fair approach to running their business. Some workers, if asked, might confide that their position in American society necessitated its most popular compromise: work or starve. They might say they are not in this country to enjoy life but to make money for their families, a sort of complicity bred of necessity in an insular and disenfranchised immigrant world. This is the effect of false promises; enduring the hard work that presses masses against the glass doors that harbor the American Dream, locked away, in view, and just out of reach, may someday pay off. Mok Sim Tsang was one such worker, another immigrant woman hidden from the collective American conscience, invisible to the masses save for the product of her labor.

Tsang met Singer in 1963 at Dana Sportswear, a sweatshop at 50 Eldridge Street. By now Singer’s efficacy in the factory had waned substantially, having been graduated by her younger, electric cousins, more efficient models whose needles moved so fast they barely had time for workplace banter their mouths were so full of fast-moving yardage. Alongside thousands of other Chinese immigrant women, Tsang made garments for piece rates paid by employers. And, like many of her peers, she had never operated industrial sewing machinery. Sweatshop work proved grueling, familiar to an old Singer, though the machine could tell this new operator had much to learn.

In the summer, the “sweatshop” moniker rang true—in the winter, it became a misnomer, and Tsang found her hands locking up as the clanging heater offered up a pittance of warmth. She would clock in around nine in the morning and rush out around six (to her five children, as Singer would come to find), while her coworkers and their machines sewed the evening away; Singer, forcibly retired, observed the new worker from afar, casting judgment from the corner of disuse she’d been stashed—three decades of intensive use had consigned her to obsolescence, and she spent most of her days listening to the same three Cantopop cassettes the women would soundtrack their work to. The subject of her scrutiny must have been in her mid-thirties, placing her a tad older than Singer who, disapprovingly, thought this human must have had somewhere more important to be; machines like Singer, despite her run-down state, respected those who could work like they could—methodically, efficiently, infinitely.

In time, and much to Singer’s surprise, Tsang, a mother hardened by oceans crossed and no stranger to the merits of hard work, caught the attention of the sweatshop foreman. She became a more specialized serger, graduating to Singer’s newer, bulkier cousins, the overlock sewing machines. She toiled even longer hours, creating precise, finished seams, working later and later hours, departing the lint-filled factory carrying aching shoulders, a sore back, a heaving cough, and the promise of a few American dollars by week’s end. The drudgery came bearing one gift—in recognition of her rising talents, the foreman offered to send her home with an old, discarded machine, no longer suitable for the factory floor. Singer was sent home with the worker she once censoriously disregarded.

The acrid stink of human urine, more specifically the souring that occurs after it has soaked a surface time and time again into a state of perpetual saturation, would have permanently seared her nostrils if Singer could smell. The pee-soaked elevator of the NYCHA housing project at 170 Madison Street (which Singer would ride exactly two times, once up and once down), lifted her an indeterminate number of floors. Tsang, and a man who Singer thought could be either her husband or her father, rolled her down a dingy hallway, past a defunct garbage incinerator that gurgled at her unintelligibly, then into an apartment that, if Singer could smell, might have evoked a sense of comfort in her cold, cast-iron body. As she rolled through the entryway, the combined scent of scallions, ginger, old wok oil, mothballs, incense, and baby powder parted like a heavy curtain, revealing a modest living room with two sunken-in couches, and a peppering of plants huddled around a large window, flanked by a tube TV in one corner and an asymmetrical tower lamp in the other. Tsang positioned Singer next to the lamp and dusted off her hands proudly—the money she would save! Raising five children on the wages of a garment worker and a restaurant worker, who Singer would eventually discover to be Tsang’s husband, proved the ultimate challenge in thriftiness, and she looked forward to outfitting herself and her children in homemade clothing using the excess textile the factory would otherwise discard.

Singer had never been in a home before nor had she ever expected to be, having resigned to her fate as an industrial machine. The tower lamp bid her a cantankerous welcome, as did the other inanimates in the home. Before the sewing machine could fully wrap her proverbial head around the concept of “home”, a red quilt, apologizing for his abrupt and nonconsensual contact, was laid over her.

After some time, Tsang put Singer to work, a labor rooted in tenderness rather than toil. When not in use, Singer and her table were covered by the quilt, and, for the most part, she could only hear the life being lived around her, though the quilt, who could see both inside and outside of himself, did a fair job of describing what Singer was missing—when Tsang would peel back the quilt, Singer would be put to work once more, focused on the clothing she and her operator were stitching. Pinstripe or plaid two-piece suits for her sons, You Mon and Jimmy, auspicious manifestations for their future as successful businessmen. Cacophonous and colorful multi-pattern quilted jackets for her middle daughters, Lucy and Susie, to match their buoyant personalities. A red sash sewn into the waist of Sui Ling’s low-rise bell bottom jeans to cover her eldest daughter’s exposed belly button. And so on, until the children became teenagers, discovering Canal Jean Co., Members Only, and Jordache, shirking their mother’s efforts, as teenagers do. With the kids exercising their preferences for the fashion of 70’s New York, Tsang lay the red quilt over Singer for the final time, a welcome retirement rather than a forceful one. The machine allowed itself to rest, indefinitely, and eventually, she, as the quilt conveyed to her, rode the elevator for the second and final time, rolling out into the natural world.

As Singer accumulated her dust over years of storage in the dark, she reflected on the maternal provisioning of her final working years, parsing her memory for those particular pieces and the children who wore them. She wondered what the children were wearing and if they had saved the clothing she had made for them. She thought of her operator, Mok Sim Tsang. She wondered what happened to her friend, the red quilt.

In 2019, Singer found herself featured in a museum exhibit exploring how labor movements changed New York City. From the signage around her, one could learn that, in 1982, twenty-thousand immigrant women in Chinatown protested against sixty garment manufacturers who refused to sign their union contracts, after decades of working long hours for low pay without childcare or protection from workplace abuse. Their demonstration succeeded in getting all firms to sign the contracts, though garment work remained challenging due to a proliferation of non-union shops in Brooklyn and global competition. Still, this shared activism transformed the garment workers union, the Chinese American community, and the women themselves, leaving a lasting mark on New York's growing Asian American communities.

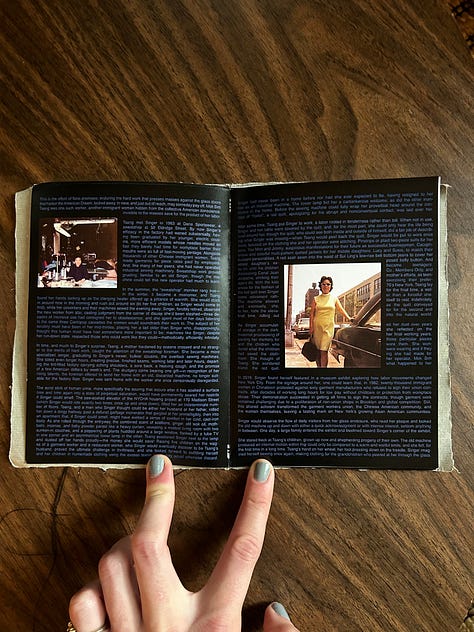

Singer would observe the flow of daily visitors from her glass enclosure, who read her plaque and looked the old machine up and down with either a quick acknowledgment or with intense interest, seldom anything in between. One day, a large family entered the exhibit and beelined toward Singer’s corner of the exhibit.

She stared back at Tsang’s children, grown up now and shepherding progeny of their own. The old machine produced an internal motion within that could only be compared to a warm and wistful smile, and she felt, for the first time in a long time, Tsang’s hand on her wheel, her foot pressing down on the treadle. Singer imagined herself sewing once again, making clothing for the grandchildren who peered at her through the glass.

When I opened Frog’s first issue for the very first time at its release party this past Sunday, I immediately choked back tears. Thank you to the Frog team for including photos of my grandmother and trusting me to take up 4 entire pages of an independently published, handprinted, and handbound magazine with her Singer’s story.

Frog Mag is here.