Often, I’ll look down past my collarbone and check Budai for cracks in his belly. I’ll roll the jadeite pendant around my forefinger and thumb and feel its familiar grooves, tracing the microns that make up his handless arms and sparsely detailed face. After so many years carrying him around my neck, these check-ins have become automatic, unconscious muscle memory. Nearly translucent with a gentle green hue, my fat stone buddha appears almost soft. He sags heavy in his brass backing, hung from a variety of gold chains, lost and replaced over the years. My mother entrusted me with it, just as her mother had her. An ever-present family heirloom that feels like an extension of myself culturally and, now, physically. I take him off only to sleep, when I know I’ll be safe from outside influence.

My cousins and I all received a piece of jade when we were children, non-exhaustively forged in the image of buddha, a donut, or a teardrop. Whether on the wrist or around the neck, Chinese folk believe jade to provide ultimate protection from danger, its heavenly power a shield from external forces seeking to damage one’s mind and body. According to Kent Wong, a luxury jeweler in Hong Kong, “jade usually represents good health and long life for Chinese people,” additionally believed to bring the wearer blessings from the gods, the ability to avoid evil, and, of course, good luck.

The stone referred to most often as Jade actually refers to two types of minerals: nephrite and jadeite. Nephrite tends to appear resinous, while jadeite is more glass-like. Their physical composition lends itself to the belief in their vitality-boosting and protective effects - jadeite is a tight arrangement of grainy crystals, and nephrite is made up of fibrous crystals that interlock in a densely packed texture - both minerals are extremely resistant to fracturing.

The Chinese proverb, “gold has value; jade is invaluable,” references those intangible, irreplicable benefits that jade may additionally bestow upon its wearer (on top of that bling-bling, baby!). Confucius wrote of jade as a manifestation of virtue, with its brightness symbolizing Heaven. An ancient Han scholar, Xu Shen, extolled that jade symbolizes wisdom, justice, compassion, modesty, and courage; the five core virtues of humanity. We Chinese relish a physical embodiment of virtue; the color of the clothing we wear is as important as the direction our bed is facing. The wealthiest nobles throughout the Han Dynasty would be buried in intricate jade suits made of thousands of separate tiles linked together with threads of gold. An opulent display of wealth, and a universal belief in jade’s protective and preservative powers. I figure jade funeral wear is largely out of trend these days, but regularly wearing a small piece on one’s person is manageable enough for the masses. The belief is that the jade will crack when it absorbs the impact of a malicious event, nobly sacrificing itself as it imparts its unbreakability to you, as you continue down your life’s path, unfettered, vis a vis an Italian horn charm protecting one from Malocchio - “evil eye”.

And while we may dismiss some of our family’s superstitions as silly, this belief in the supernatural builds a cross-generational bridge for immigrant elders to provide children a connection to their homeland.

I find that we first and second-generation immigrants can be what I like to describe as “selectively superstitious”. Perhaps due in part to cultural assimilation in action, we may find ourselves thinking outside the bounds of demarcated systems of belief, a byproduct of our multicultural environment and upbringing. In an Oxford study offering perspectives on the cultural integration of immigrants, researchers posited the acculturation strategies that individuals in minority groups employ in identity formation. The first strategy is integration, which “implies a strong sense of identification to both the original and the majority culture.” We may cherrypick those tenets that our aunties believe with supreme superstition and integrate them into a worldview informed by both our grandmothers and our peers. And while we may dismiss some of our family’s superstitions as silly, this belief in the supernatural builds a cross-generational bridge for immigrant elders to provide children a connection to their homeland.

A widely held superstition in Korea is “fan death” - the belief that if one falls asleep with the electric fan or air-conditioning on, they’ll die overnight. A chilling thought, but according to Katie Heaney in The Atlantic, there are those who “suggest that the fan death myth was even propagated by the South Korean government to curb the use of electricity during the 1970s energy crisis”. Writer Jinnie Lee explained this inherited superstition from her parents.

“It was a myth they inherited from their own parents (and their Korean culture). Fan death is one of the many Korean oddities that had seeped into my American upbringing.”

Upon discovering as a child that fan death did not occur whilst sleeping over at an American friend’s home, Lee was faced with the revelation that, as a child of immigrants, she could be selectively superstitious while still respecting the beliefs of her parents.

“On the hottest days, when I think I might sweat myself to dehydration in Brooklyn, I call my mom to see how she’s doing over in New Jersey. She has devised her own system: She sets her alarm that wakes her up at various times during the night so she can turn the A/C on and off at intervals. That seems really annoying, I tell her. This is the only way, she responds.”

These ornamentations and behaviors act in opposition to the supposed unrelenting and pervasive potentiality of catastrophe besieging humanity at all times.

A marked character of Chinese superstition is its emphasis on spiritual protection and material prosperity, non-exhaustively manifested in object arrangements, numbers, and colors, with one dated superstition even going so far as to recommend piercing the ears of little boys and letting their hair grow long so that the earrings or pigtails they wear might confuse evil spirits, mistaking them for little girls who they supposedly have no use for; though I, for one, believe little girls should be abducted by evil spirits just as much as little boys. This is why we need to all be wearing our jade earrings, y’all! These ornamentations and behaviors act in opposition to the supposed unrelenting and pervasive potentiality of catastrophe besieging humanity at all times. The Yin and the Yang, I suppose.

Whenever my mother visits, she’ll pull out her proverbial Feng Shui detector and critique my room arrangement, remarking that I should “move the bed so my feet aren’t pointed out the door,” lest my chi be sucked out of my bedroom as I sleep, or, “hang my mirror on that other wall”, disregarding the fact that there isn’t another wall (living in New York City rarely begets optimal energy flow). My eyes roll to the back of my head as we head to Chinatown for dim sum, though I make sure to don my jade necklace for protection before we depart.

There is a distinctive liberation in choosing which spiritual beliefs to equip on one’s life journey. I don’t believe the positioning of furniture matters in the grand scheme of my health and wellness, though I do believe in the spectral protection a piece of jade bequeaths. Perhaps contradictory, perhaps extricated, I have selectively deemed true the belief that my heirloom necklace acts as a conduit to the beyond while shirking other superstitions.

With her influence bound to me only by jade, I’ve also had to form a connection to a woman I never had a chance to know - my po-po, my mother’s mother. I believe my grandmother to be staunch and stoic, yet loving and kind. She would have to be infallible, as I assume any spiritual guardian should. My grandmother, an immigrant from Guangdong, arrived in New York speaking only her native Cantonese and proceeded to raise her five children largely alone in the Canto/Fuzhounese bastion of Manhattan Chinatown. She believed in the Buddha, and I believe in her through my jade effigy.

I don’t necessarily believe the simple mineral makeup of my Budai necklace offers provides me apex protection - it’d be just a pretty trinket to me without the cross-generational connection to my mother’s mother, an ancestral presence that I’ve only been able to form in the vacuum of my head. If I were to twist Budai around in my pointer finger and thumb to find a crack in his belly, I would know that po-po had intervened between me and some unseen force of maleficence.

It’s a good thing I believe she’s always watching. Who knows what could’ve happened?

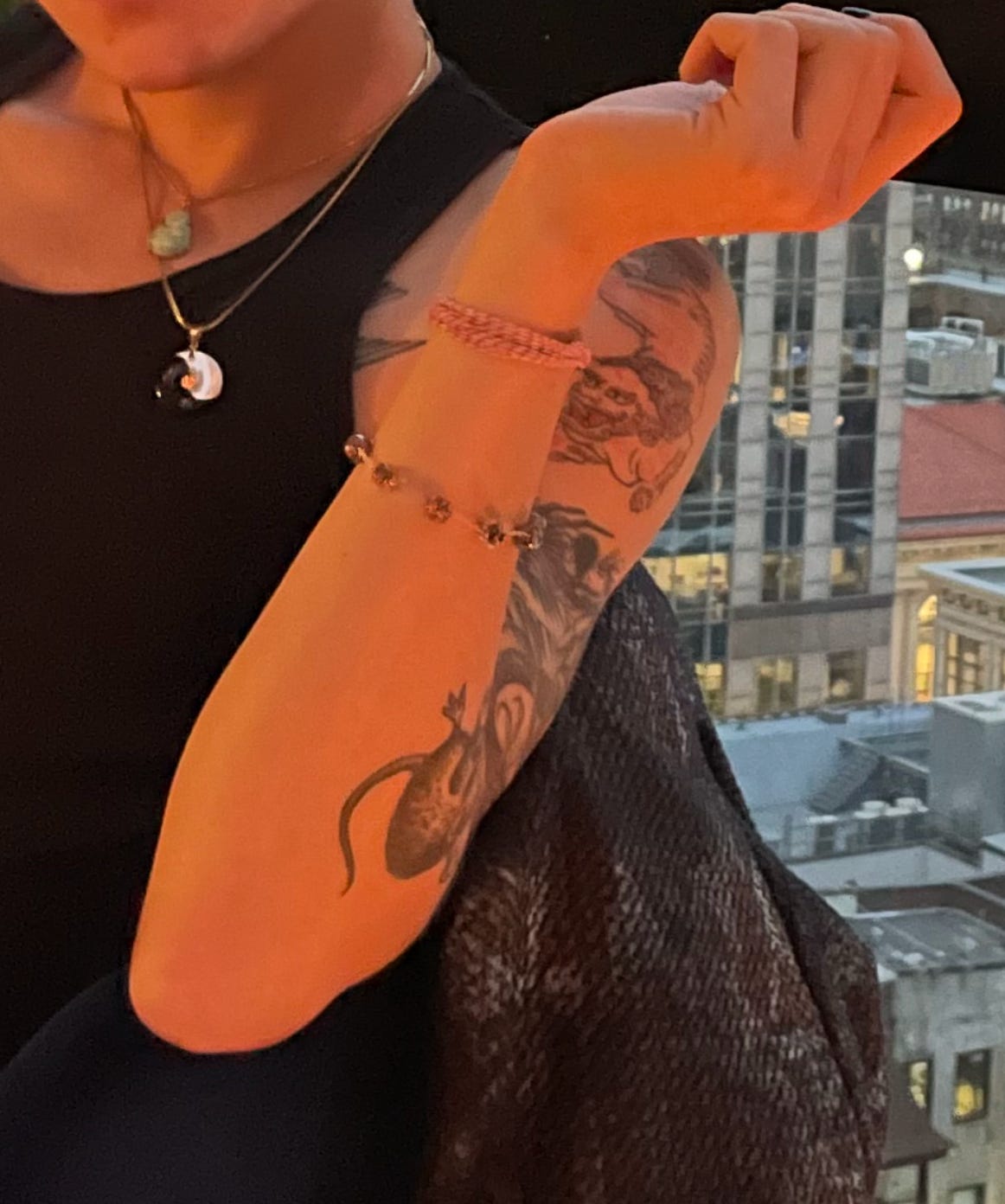

Your grandma is watching, is loving the jade wearing, trying to keep quiet about the tatoos, but liking the thoughtfulness of all this.